Reflecting on Michael Porter’s Value Chain theory from 1985 and our initial idea of a value hub in 2012, which evolved into the Value Actor, we’ve embarked on an intriguing exploration. Could the chain analogy, especially in the context of individual performance measurement, have inadvertently fostered the creation of functional silos? We propose an innovative, unconventional solution to this challenge. If you’re unfamiliar with Porter’s Value Chain theory, it’s worth delving into this foundational concept for a deeper understanding.

The Missing Link in the Value Chain Theory

With its innovative analogy of interlinked activities providing a competitive advantage, Michael Porter’s Value Chain theory presents a complex web akin to a tangled pile of chains. This intricate network illustrates the myriad of known and unknown interdependencies within a company’s operations. However, while effective in strategizing value creation, this model overlooks the human element. Assessing individual contributions becomes challenging when many factors lie outside an employee’s control. Recognizing this gap is crucial, as overlooking it risks unfairly evaluating talent based on systemic issues rather than individual merit. This highlights the need for a more nuanced approach considering business operations’ systematic and human aspects.

Value Hubs, Networks and Actors: Rethinking the Value Chain

Reflecting on our Customer Lifecycle Mapping and the value hub concept, we see that every activity essentially forms its own Value Hub. Each hub encapsulates the familiar Input, Process, Output, and Feedback pattern. This realization casts each entity as a self-contained hub of value creation, executing a specific job at a defined cost.

Each entity relies on inputs to generate outputs through its unique processes, from a hospital improving patient health to a building company constructing offices. However, the ecosystem of value hubs isn’t isolated; they require interconnectedness to thrive. Their sustainability hinges on continuously exchanging inputs and outputs, forming a network of value hubs.

This interconnectivity also necessitates feedback, turning it into a vital performance indicator, like the Net Promoter Score (NPS), ensuring the value created adapts to evolving needs and expectations.

Schematic of a Value String

Envisioning the frontline as a series of interconnected value hubs, where each hub’s existence is justified by its ability to meet the needs of adjacent hubs, results in a collaborative scheme. This model, comprising a sequence of value hubs, illustrates a dynamic chain of collaboration, where each hub’s output becomes the subsequent hub’s input, creating a continuous granular flow of value through the system.

And by grouping a series of value hubs, we get a department. And if we consider that all value hubs form a trainset, we get a value train. Let’s take the frontline activities as an example:

To effectively measure the performance of each value hub, the Rate of Satisfaction (RoS) becomes a pivotal metric. This is gauged by feedback from the receiving value hub. Such a streamlined assessment method simplifies the evaluation process and quickly highlights areas needing improvement.

When a change in the overall performance of the Value Train – the sequence of frontline processes – is detected, the RoS indicators paint a clear picture. This allows for prompt, targeted interventions at the value hub level, showing the greatest need, ensuring continuous optimization of the entire process.

While the Rate of Satisfaction (RoS) metric offers valuable insights into the performance of individual value hubs, it’s just the beginning of the story. It pinpoints where to focus our analysis, but a deeper investigation is needed to understand the root causes of satisfaction changes.

When multiple value hubs exhibit similar shifts in RoS, it may, for instance, indicate shared interdependencies. A Value Chain Analysis becomes essential to examine primary and support activities and their sub-activities in direct operations, indirect influences, and quality assurance.

The Value Chain theory remains vital, particularly when combined with the VRIO framework for sustaining competitive advantages. However, its utility lies more in strategic analysis than in measuring individual performance or swiftly identifying human causes behind sudden performance changes.

Introducing the Value Track

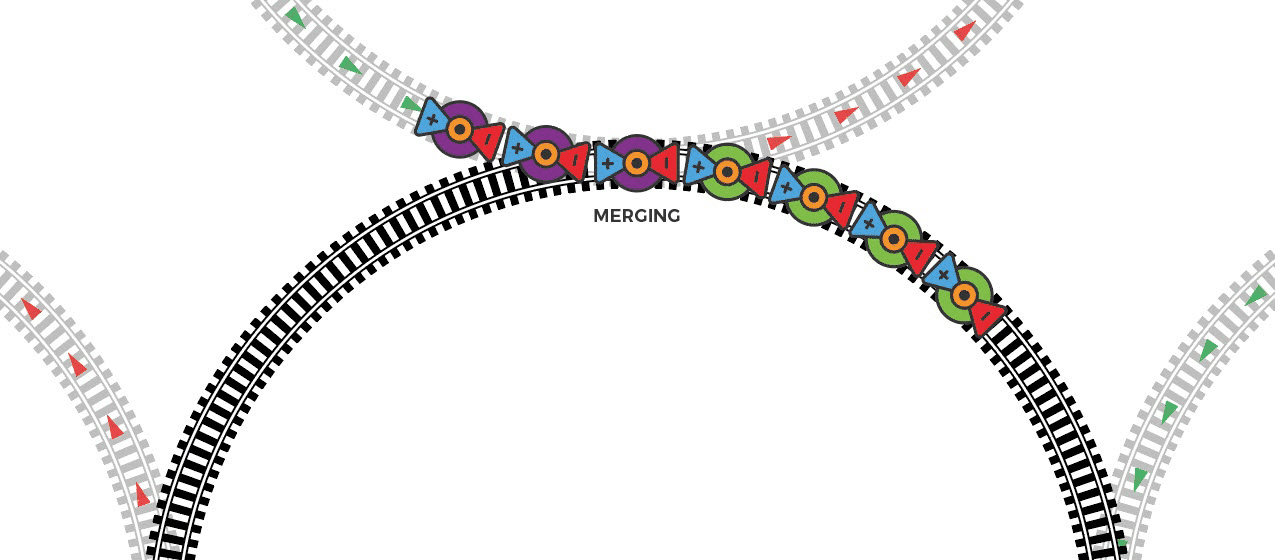

Imagine the Value Train concept as a train on a track, perfectly embodying the RoundMap philosophy with its circular path. The seller’s Value Train, symbolized by green wheels, circles its major Value Hub, signaling its value to attract a buyer’s Value Hub, depicted with purple wheels.

As the seller’s train guides the buyer’s train through various departments, the buyer assesses if the seller can fulfill its needs. If unconvinced, the buyer’s train detaches, seeking other opportunities.

This dynamic is illustrated by green arrows indicating attraction and red arrows signifying disconnection, a vivid representation of the evolving value-based relationships in business.

Final Thoughts

Shifting from a transactional to a relational approach in business is akin to transforming a monotonous circular track into an evolving spiral. In a relational model, feedback becomes a catalyst for compound learning, driving progressive development in an upward spiral toward greater significance and meaning.

Conversely, neglecting this approach or a decline in performance could lead to a downward spiral, which typically accelerates much faster. This notion underscores the importance of continuous improvement and meaningful connections in business dynamics. Your thoughts on this concept would be enlightening.

Author

-

Edwin Korver is a polymath celebrated for his mastery of systems thinking and integral philosophy, particularly in intricate business transformations. His company, CROSS-SILO, embodies his unwavering belief in the interdependence of stakeholders and the pivotal role of value creation in fostering growth, complemented by the power of storytelling to convey that value. Edwin pioneered the RoundMap®, an all-encompassing business framework. He envisions a future where business harmonizes profit with compassion, common sense, and EQuitability, a vision he explores further in his forthcoming book, "Leading from the Whole."

![The ValueTrain: Navigating the Circular Path of Value Creation 1 ROUNDMAP_ValueTrain_ValueHubs[1]](https://roundmap.com/wp-content/uploads/ROUNDMAP_ValueTrain_ValueHubs1.jpg)

![The ValueTrain: Navigating the Circular Path of Value Creation 2 ROUNDMAP_ValueTrain_Concept_ValueHub_Train[1]](https://roundmap.com/wp-content/uploads/ROUNDMAP_ValueTrain_Concept_ValueHub_Train1.png)

![The ValueTrain: Navigating the Circular Path of Value Creation 3 ROUNDMAP_ValueTrain_Concept_ValueHubs_RoS[1]](https://roundmap.com/wp-content/uploads/ROUNDMAP_ValueTrain_Concept_ValueHubs_RoS1.jpg)