Professor Thales Teixeira from Harvard Business School took 8 years to write his book ‘Unlocking the Customer Value Chain: How Decoupling Drives Consumer Disruption’. His observations of dozens of startups, tech companies, and traditional players led to an understanding of how business is being disrupted. We’ll discuss his findings while uncovering the question: Why now?

The Customer Value Chain

The publisher explains: “There is a pattern to digital disruption in an industry, whether the disruptor is Uber, Airbnb, Dollar Shave Club, Pillpack, or one of the countless other startups that have stolen large portions of market share from industry leaders, often in a matter of a few years.”

“As Teixeira makes clear, the nature of competition has fundamentally changed. Using innovative new business models, startups steal customers by breaking the links in how consumers discover, buy, and use products and services. By decoupling the customer value chain, these startups peel away a piece of the consumer purchasing process instead of taking on the world’s Unilevers and Nikes, BMW and Sephoras head-on.”

A Customer Value Chain is a business concept that represents creating value for a customer. It is similar to the supply chain, which charts the various stages of production and supply, from raw materials to the sale of the final good to the end user. The big difference is that while a supply chain often measures costs, the customer value chain is based on the end user’s value increase.

This idea is somewhat similar to a ‘value stream.’ Value streams describe how a stakeholder – often a customer – receives value from an organization. As opposed to many previous attempts at describing stakeholder value, value streams take the perspective of the initiating or triggering stakeholder rather than an internal value chain or process perspective.

What Uber, Amazon, and Airbnb have in common is that they aim to make the customer’s job much easier. Uber made ride-hailing a breeze, Amazon made it simple to search for exotic books, and Airbnb made it effortless to find a cheap and fun place to stay. They all took the customer’s job to be done as a starting point and created a service that significantly improved customers’ lives.

Decoupling of Work and Craftmanship

Around 1890, Frederick Winslow Taylor was one of the intellectual leaders of the Efficiency Movement, a pioneer in applying engineering principles to the work done on the factory floor.

What Taylor described, often referred to as the division of labor, was, in fact, the decoupling of work and craftsmanship. Instead of having to hire exceptional people with a broad skill set, he suggested breaking down work into smaller pieces. This allowed a factory manager to hire much cheaper specialists, easier to train and replace, more skillful, and therefore more productive.

Throughout the years, we’ve applied the same scientific management principles to factory workers and the entire organization. Even today, people are compelled at a young age to choose their area of specialization. Polymaths are not allowed.

From Compartmentalization to Siloization

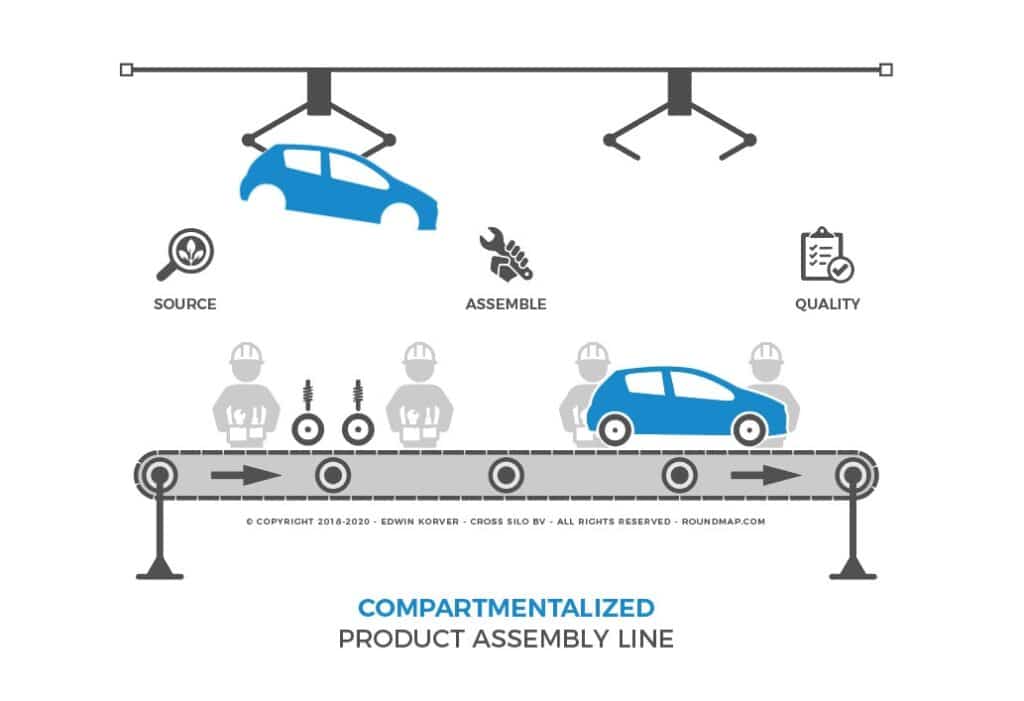

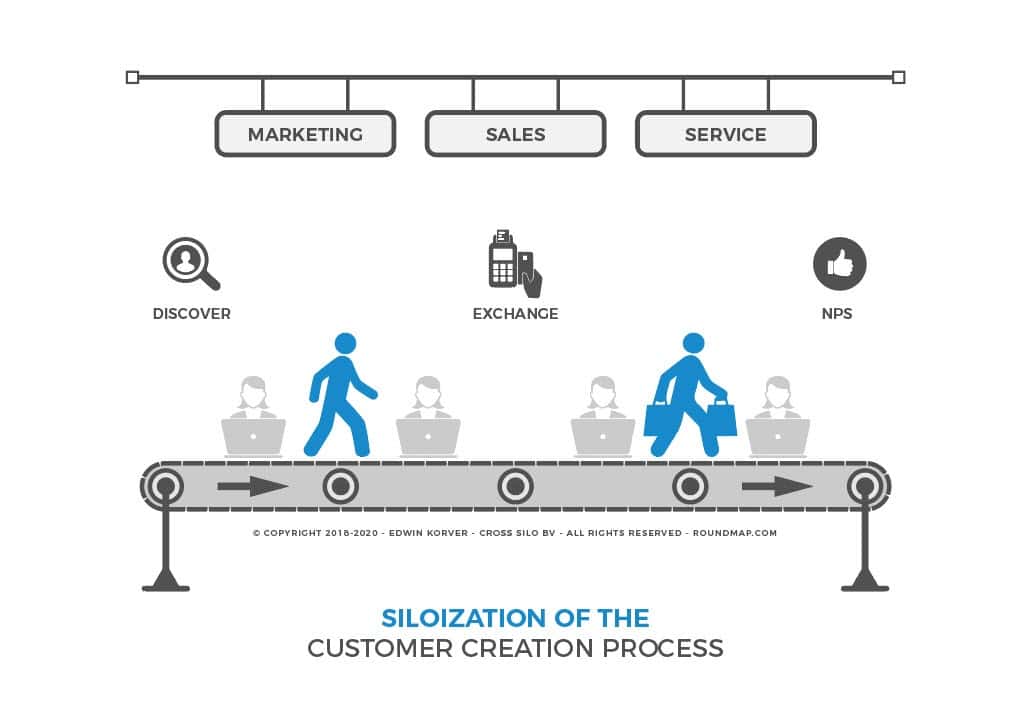

The compartmentalization that initially emerged on factory floors during industrialization mirrors what has happened in front-line organizations today. The legacy of Frederick Taylor’s division of labor is not confined to the manufacturing process but has also been extrapolated to customer-facing roles. To clarify this analogy, one can think of the traditional factory as a microcosm of the larger organizational structure, with its distinct “customer journey” elements.

Factory Floor vs Front Line: A Comparative Examination

-

Sourcing of Materials vs. Discovery of Market Potential: Just as materials are sourced to initiate production in a factory, market research and discovery serve as the foundational elements for front-line organizations.

-

Assembly Line vs. Exchange of Value: In factories, assembly lines are the core mechanisms that add value to raw materials. Similarly, front-line employees add value to the organization by effectively “assembling” solutions for clients, facilitating the exchange of value between supply and demand.

-

Quality Control vs. Customer Satisfaction (NPS Score): The final product undergoes quality checks in the factory, much like the customer’s journey ends with an evaluation via metrics like NPS scores.

Consequences for Disengagement and Alienation

-

Narrow Focus, Reduced Ownership: Compartmentalization can lead to a narrow focus on specific tasks on the factory floor and in front-line roles. If engaged in a more comprehensive role, this reduces employees’ sense of ownership and accountability.

-

Disconnection from End Value: When an individual is only a tiny cog in a giant machine, it cannot be easy to perceive how one’s work contributes to the end value for the customer. This disconnect can lead to disengagement and a diminished sense of purpose.

-

Emotional Distance from Outcomes: Front-line employees, much like factory workers, can become emotionally detached from the end customer if their roles are narrowly defined and they don’t see the full impact of their work.

-

Cultural Inertia: Once compartmentalization becomes culturally ingrained, shifting toward a more integrated and engaged workforce can be challenging. This inertia perpetuates disengagement and can make any transformational efforts more challenging.

-

Loss of Skill Diversity: Just as the specialized factory worker loses the craftsmanship of yore, front-line workers may not develop a diverse range of skills, limiting their adaptability and potentially job satisfaction.

By drawing parallels between the factory floor and front-line organizations, we highlight the pervasive risk of disengagement and alienation, which spans multiple dimensions of work. This analysis calls for a more holistic approach to organizational design, prioritizing engagement and a sense of purpose across all roles and functions.

Risks of Decoupling

The risk here is that companies may be undermining a sense of holistic engagement by isolating specific aspects of the customer experience. Employees in such organizations might find it challenging to appreciate the broader impact of their work on customers’ lives because they are narrowly focused on a specific task or service.

Here are some potential outcomes of digital decoupling:

Reduced Employee Commitment: Employees who don’t see the complete picture of how their contributions affect the customer may feel less committed to the organization’s broader mission.

Lower Empathy Levels: Narrow scopes of work might mean that employees are less inclined to consider the customer’s overall journey, thereby impacting the level of empathy they might naturally extend.

Customer Frustration: Just as employees might not see the whole picture, customers too may get frustrated interacting with multiple entities for what they perceive as a single need. This could reduce customer loyalty and engagement over time.

Impersonal Interactions: The more specialized the roles, the more scripted they often become, which could result in impersonal, transactional interactions that fail to engage the customer emotionally.

Conflicted Organizational Culture: Organizations that pride themselves on delivering exceptional customer service might find digital decoupling conflicts with their core values, affecting overall culture and morale.

While digital decoupling offers efficiencies and opens market opportunities for startups and established players alike, a nuanced approach is necessary to counter potential alienation and disengagement. This could involve cross-training employees, fostering a culture that encourages understanding the broader customer journey, and leveraging technology to create more personalized and meaningful customer interactions.

So, while Professor Teixeira’s observations provide valuable insights into the operational aspects of digital decoupling, the long-term effects on employee and customer engagement represent an area ripe for further study and consideration.

In Pursuit of Scale Economies

While the division of labor raised productivity, complexity increased alongside it. Companies had to expand their operation quickly to offset the operating costs and make a profit. More production led to more stock and drove companies to sell more products ─ leading to mass consumption.

Economies of Scale meant that only the largest operations could compete successfully on price, causing an evergrowing economic divide. Between 1978 and 2012 the share of startups relative to industry leaders dropped by as much as 44 percent, while employee wages remained almost the same.

In 2012, the Kauffman Foundation launched the ‘Startup Act‘ to incite people to start new businesses:

The Tipping Point

Let’s go back to our question: Why is this happening now? How could these startups disrupt markets and industries under incumbents’ control for so many years?

As incumbents increased their portfolio to serve more diverse markets, their operations grew in size. Work had to be divided to raise productivity, creating complicated structures of specialist teams. By sharing resources and capabilities between separated departments and divisions, duplication could be prevented, allowing efficient utilization.

However, sharing introduced complex interrelationships that brought new restraints, decreasing operational agility. Consequently, these corporates have a tough time coping with fast-changing customer demand. Although most perceive themselves as too big to fail, they are, in fact, most vulnerable to disruption.

So, again, why now? Contrary to the traditional value chain, the digital value chain is still undeveloped. This allows digital-savvy entrants to focus on a single aspect of the digital value chain, decoupled from its entirety, and offer unsurpassable added value. For instance, Backbase is a Dutch startup focused on offering a superb digital banking experience, allowing banks to deploy it as a front-end, interfacing with the bank’s legacy systems ─ allowing the client to focus on its core business.

Beware, the traditional value chain went through a similar process of decoupling decades ago, giving rise to specialists like distributors, cargo handlers, warehouses, accountants, and print services.

What's Behind the Horizon?

Although we are still in a transitional phase ─ in between two large s-curves, the cards will soon be reshuffled. Most incumbents will need to restructure, while some will disappear. As the next s-curve takes shape, new corporates will emerge, however, contrary to the current cohort of ventures, they will need to coexist in an environment that is far more cooperative, distributive, and regenerative.

Our planetary resources won’t sustain the rising demand as the population rises. In 1905, the average person consumed 4.6 tons of resources; today, that’s more than 10 tons. This exponential growth is not only causing environmental havoc, but it’s also depleting Earth. We need another form of decoupling: the decoupling of wealth and resources to survive another century of consumerism.

As we’ve uncovered via the Business Model Matrix, resource-centric or network-centric business models are the way to a more sustainable form of consumption.

Author

-

Edwin Korver is a polymath celebrated for his mastery of systems thinking and integral philosophy, particularly in intricate business transformations. His company, CROSS-SILO, embodies his unwavering belief in the interdependence of stakeholders and the pivotal role of value creation in fostering growth, complemented by the power of storytelling to convey that value. Edwin pioneered the RoundMap®, an all-encompassing business framework. He envisions a future where business harmonizes profit with compassion, common sense, and EQuitability, a vision he explores further in his forthcoming book, "Leading from the Whole."