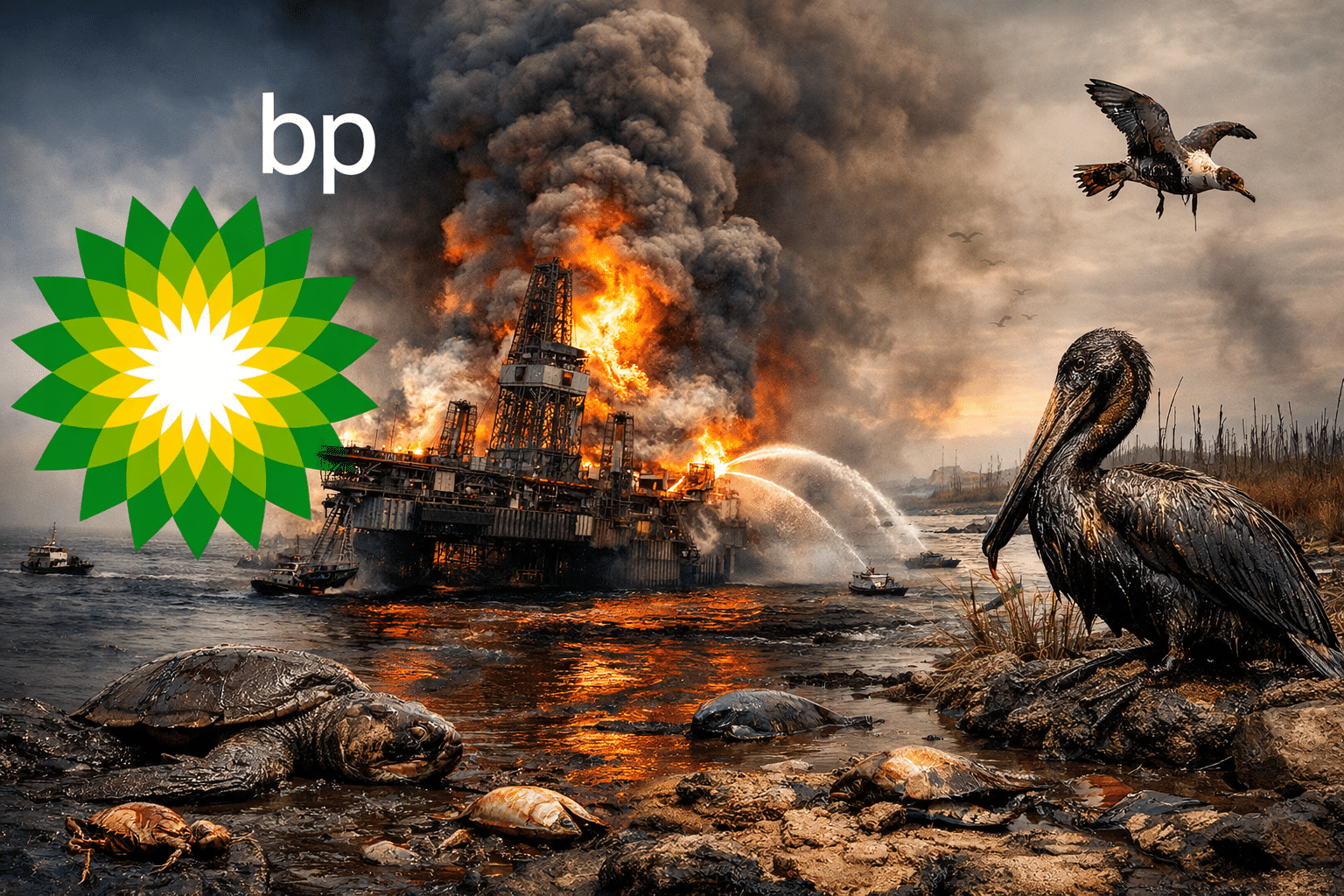

In April 2010 the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig, operated for BP by Transocean, exploded off the coast of Louisiana, killing eleven workers and unleashing one of the most devastating environmental disasters in U.S. history. What may at first appear as an industrial accident was, on closer inspection, a failure of organizational logic — where the dominant premise of value creation became entangled with egocentric capture and the externalization of cost.

Profit Pressure as a Root Cause

Leadership and Cultural Signal

BP’s leadership narratives reflected a consistent prioritization of efficiency and economics — even in safety-critical environments. Research on BP’s leadership rhetoric shows that cost containment and operational efficiency dominated CEO communication, often overshadowing safety discourse. This kind of messaging doesn’t just signal priorities in a vacuum — it redefines organizational sensemaking, leading teams to internalize that financial performance is the foremost metric of success. ScienceDirect

Former CEO Tony Hayward, who led BP during the incident, once famously articulated that a company’s “primary purpose … is to create value for our shareholders,” even while asserting commitments to broader responsibilities — a contradiction that reflects deeper systemic tensions in corporate logic. Wikipedia

The Cement Test and Risk Choices

Central to the mechanical failure was the cement barrier intended to seal the Macondo well. Independent analyses have found that the cement bond was inadequate and that additional testing — which would have taken time — was not performed. A more thorough testing regime was standard in other offshore operations but was skipped here, in part because of cost and schedule pressures that discouraged extended evaluation. Madison N. Fujii

In many respects, this reflects a classic tradeoff error where immediate financial metrics were given precedence over rigorous risk assessment — one that would have mitigated known hazards but delayed completion. This wasn’t an isolated technical misstep; it was embedded in a risk culture where speed and budget control were framed as priorities. Madison N. Fujii

Systemic Externalization of Cost

While shareholders reaped dividends and valuation gains in the years leading up to the crisis, and the company catalogued a “golden period of expansion” under its previous CEO (John Browne), these benefits were realized through practices that deprioritized safety investments and oversight. The rigorous inspections and engineering checks that might have revealed critical vulnerabilities were scaled back in pursuit of efficiency. Studocu

The true costs — ecological devastation, loss of biodiversity, ruined livelihoods across Gulf Coast communities, and long-term economic fallout — were externalized to society and natural systems. The NOAA and other agencies documented extensive damage to marine ecosystems, fisheries, migratory birds, and coastal habitats — impacts that persist years later and are immeasurable in purely economic terms. Wikipedia

Consequences and Feedback Loops

When the spill occurred, BP faced tens of billions in liabilities, asset divestments, reputational devastation, and sharp drops in market value. Yet the initial corporate logic that led to the disaster — cost-centric decision-making and narrow shareholder value orientation — was not unique to BP; it is pervasive in many large multinational firms. Wikipedia

This underscores a profound systemic contradiction: a system designed to generate “value” for a narrow set of stakeholders can degrade broader ecological and social systems — ultimately diminishing true resilience and long-term value for all.

A Broader Lesson: Where Value Logic Went Wrong

What BP’s case illustrates isn’t just bad management — it’s a flawed premise of value creation:

-

Financial supremacy over systemic health: Prioritizing shareholder metrics and cost efficiency created incentives that masked systemic risk.

-

Short-term gains vs. long-term resilience: Choices optimized for the next quarter ignored latent hazards that required time, attention, and investment to mitigate.

-

Internal success, externalized costs: The company captured economic benefits while outsourcing environmental and social costs to communities and ecosystems — a distortion of what “value” actually means.

In regenerative or whole-system paradigms, value isn’t extracted from a system only to be captured narrowly; it’s co-created with and returned to the environmental, social, and economic systems it touches. BP’s story is a powerful example of what happens when that balance collapses.

From Creation to Circulation: The Ownership Fallacy

At the heart of this failure lies a deeper illusion: the belief that corporations create value out of nothing and therefore earn a primary right to its capture. This premise quietly shapes culture, incentives, and entitlement. Yet nothing is created ex nihilo. Every so-called act of value creation is, in reality, an act of transformation and circulation—using materials, energy, knowledge, infrastructures, ecosystems, and social stability that already exist. Nature provides the raw surplus. Society provides the legal, educational, and institutional scaffolding. Generations before us provide accumulated insight; generations after us bear the consequences.

Business does not create value from nothing—it reconfigures what already is. From that perspective, profit cannot be claimed as owned by default. There is no natural right to exclusive capture, only a temporary role as steward and orchestrator within a living system. Progress happens not because we invent in isolation, but because we stand on layers of contribution that precede us and extend beyond us.

What we call ownership is not a fact of creation but an economic construct—taught and institutionalized as if it were a social agreement, despite the absence of universal consent or systemic reciprocity. And when that agreement ignores the system that made value possible in the first place, it collapses into extraction.

Finally, consider this:

- We are not immoral actors — we are well-trained participants

- The problem is not intent, but the premises we inherit

- Regeneration is not rebellion — it is recalibration

- Redesigning value logic is not ideological — it is systemically necessary

If value is always co-produced, then capture without circulation cannot claim legitimate ownership. What is commonly defended as profit is often unilateral appropriation—enabled by an economic construct that treats contribution as isolatable and entitlement as automatic. It is not recognized as theft because the premise of ownership itself goes unquestioned. Legitimacy, in this system, is granted by convention rather than earned through reciprocity. Yet when capture consistently exceeds contribution, ownership dissolves into extraction—whether or not the language has caught up.

Extraction is simply appropriation that has not yet been named.

Author

-

Edwin Korver is a polymath celebrated for his mastery of systems thinking and integral philosophy, particularly in intricate business transformations. His company, CROSS/SILO, embodies his unwavering belief in the interdependence of stakeholders and the pivotal role of value creation in fostering growth, complemented by the power of storytelling to convey that value. Edwin pioneered the RoundMap®, an all-encompassing business framework. He envisions a future where business harmonizes profit with compassion, common sense, and EQuitability, a vision he explores further in his forthcoming book, "Leading from the Whole."

View all posts Creator of RoundMap® | CEO, CROSS-SILO.COM