In a previous article, we introduced Value Centricity as a Viability Model—not as another business model, operating model, or revenue model, but as a means to determine whether any business model can continue over time. The central claim was that viability precedes performance: businesses do not fail because they choose the wrong strategy, but because they undermine the value flows and ecosystems that make their existence possible. When those conditions erode, no amount of optimization can restore them.

This distinction echoes the late Russell Ackoff, who repeatedly warned against the reflex to endlessly optimize existing systems. As he famously observed, “Trying to improve a bad system is a very bad idea,” and argued that at a certain point it becomes wiser to design a better system rather than continue bettering the one we have. Ackoff’s insight was not about efficiency, but about systemic fit: improvement within the wrong structure only entrenches its failure.

Value Centricity, understood as a Viability Model, provides precisely the lens Ackoff was pointing toward. It does not ask how to make a system perform better, but whether the system still preserves the conditions required for continuation. When value circulates, regenerates, and compounds across interconnected systems, improvement remains meaningful. When value is increasingly extracted, enclosed, or depleted, improvement becomes counterproductive—masking decline rather than reversing it.

From inward-looking viability to systemic viability

Traditionally, viability has been treated as an internal business question. Within the Grandmaster’s Playbook—Feasibility, Viability, and Desirability—viability has typically been understood to mean: Can we make it profitable? Does the solution sustain itself financially within the boundaries of the organization?

That interpretation made sense within a context where markets were assumed to be stable, resources abundant, and external effects largely absorbable. Viability, in this framing, functioned as a gatekeeper for execution: if something could be built (feasible), wanted (desirable), and monetized (viable), it was considered worth pursuing.

However, this definition of viability is fundamentally inward-looking.

It evaluates success from the perspective of the firm, treating the surrounding system as a given. The question it asks is whether the organization can continue—not whether the system that enables that continuation remains intact. Value Centricity reframes viability entirely.

Within the Viability Model, viability becomes an outward-looking question: Should we continue doing what we are doing—or have the conditions changed such that continuation now undermines the very systems that make value possible?

This shift is subtle, but decisive.

Rather than asking whether a business can extract sufficient returns to justify its existence, the Viability Model asks whether the business still contributes to, aligns with, or at least does not degrade the value flows and ecosystems it depends on. When that alignment breaks, profitability may persist for some time—but viability has already begun to erode.

In this sense, Value Centricity moves viability from a question of financial sustainment to one of systemic permission. Not permission granted by regulators, markets, or morality—but by the continued availability of trust, participation, resources, resilience, and meaning. When those conditions withdraw, the system answers the question on the business’s behalf.

Viability, then, is no longer about doing things better. It is about knowing when better execution is no longer enough—and when different things must be done instead.

This completes the shift implied by the Viability Model: from optimizing continuation within a system, to discerning whether continuation of the system still makes sense at all.

Why this matters now

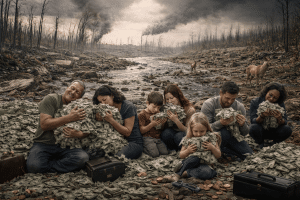

The tension between optimization and viability is no longer abstract. Supply chains are fragmenting, institutional trust is eroding, ecological limits are asserting themselves, and the social license to operate is thinning across industries. In such conditions, the central question facing business is no longer how to optimize performance within existing structures, but whether those structures still preserve the conditions required for continuation.

This is where the comparison between Value Centricity and shareholder primacy becomes unavoidable.

Optimization failure versus viability failure

Shareholder primacy is best understood as an optimization doctrine. It assumes that maximizing returns to capital is both the purpose of the firm and the measure of its success. Within this logic, as long as capital grows, the business is considered healthy—even if the conditions that enable its existence are quietly being depleted.

This logic systematically conflates two fundamentally different failure modes.

Optimization failure occurs when a system underperforms according to its own logic.

Viability failure occurs when the logic itself undermines the conditions that make performance possible.

Shareholder primacy is not failing because it is poorly executed. It is failing because it routinely converts viability risks into externalities, treating them as costs to be displaced rather than conditions to be preserved. The Viability Model reverses this logic.

In a Viability Model, continuation precedes optimization. A business is viable only insofar as it sustains the value flows and ecosystems—economic, social, and ecological—on which it depends. Profit does not disappear, but it shifts position: from governing objective to lagging indicator.

Capital becomes a dependent variable.

How Value Centricity governs viability

Under shareholder primacy:

- Value is assumed to be owned once captured

- Extraction is legitimate as long as it is legal

- Externalities are treated as peripheral

- Time horizons collapse into quarters

Under Value Centricity as a Viability Model:

- Value exists only while it continues to be conferred by the system

- Capture without circulation depletes the source of value

- Externalities are not ethical failures, but viability risks

- Time horizons expand to multi-generational effects

Crucially, the Viability Model does not rely on governance, restraint, or moral appeals to function. It operates through a simple but unforgiving mechanism: loss of conditions.

When extraction outpaces regeneration, the system does not collapse all at once. Instead, it withdraws optionality. Trust erodes. Participation declines. Resilience thins. Redundancy disappears. What vanishes first is not profit, but the capacity to respond.

This is why firms optimized for shareholder primacy can remain profitable while becoming progressively less viable—and why collapse so often appears sudden in hindsight.

A diagnostic shift

The Viability Model introduces a different kind of test. Not a performance metric, but a structural question:

Would this business model remain viable if its externalized costs were internalized over time?

If the answer is no, the issue is not competitiveness, execution, or efficiency. The issue is systemic misalignment. No amount of optimization can compensate for the erosion of the conditions that make value possible in the first place.

This is the moment Ackoff warned us about.

From bettering the system to choosing a better one

Shareholder primacy assumes that the system is fundamentally sound and merely in need of better incentives, better governance, or better execution. The Viability Model challenges that assumption—not normatively, but structurally.

Value Centricity does not argue against shareholder primacy. It renders it insufficient.

Because no claim on capital can override a simple systemic reality: business cannot extract itself into continuation.

Value Centricity makes visible the point at which improvement within the system no longer works—when bettering the system accelerates its decline—and when choosing a better system becomes the only rational move.

Not because it is more ethical. But because it is more viable.

Author

-

Edwin Korver is a polymath celebrated for his mastery of systems thinking and integral philosophy, particularly in intricate business transformations. His company, CROSS/SILO, embodies his unwavering belief in the interdependence of stakeholders and the pivotal role of value creation in fostering growth, complemented by the power of storytelling to convey that value. Edwin pioneered the RoundMap®, an all-encompassing business framework. He envisions a future where business harmonizes profit with compassion, common sense, and EQuitability, a vision he explores further in his forthcoming book, "Leading from the Whole."

View all posts Creator of RoundMap® | CEO, CROSS-SILO.COM