Strategy is often compared to the art of war, which just so happens to be the title of the book of the legendary Chinese general Sun Tzu. I will try to explain why the ancient principles of the art of war, despite its recent successes in corporate strategy, no longer apply (for the time being) and could even lead to a company’s early demise.

The Principles of the Art of War

Sun Tzu described the principles of warfare that he considered critical for any campaign to succeed. In short, an army’s strategy needed a Commander that stood for certain virtues, while his soldiers had to be in complete accord with their ruler, i.e., the Commander and follow his instruction without objection or hesitation, while maintaining certain methods and disciplines.

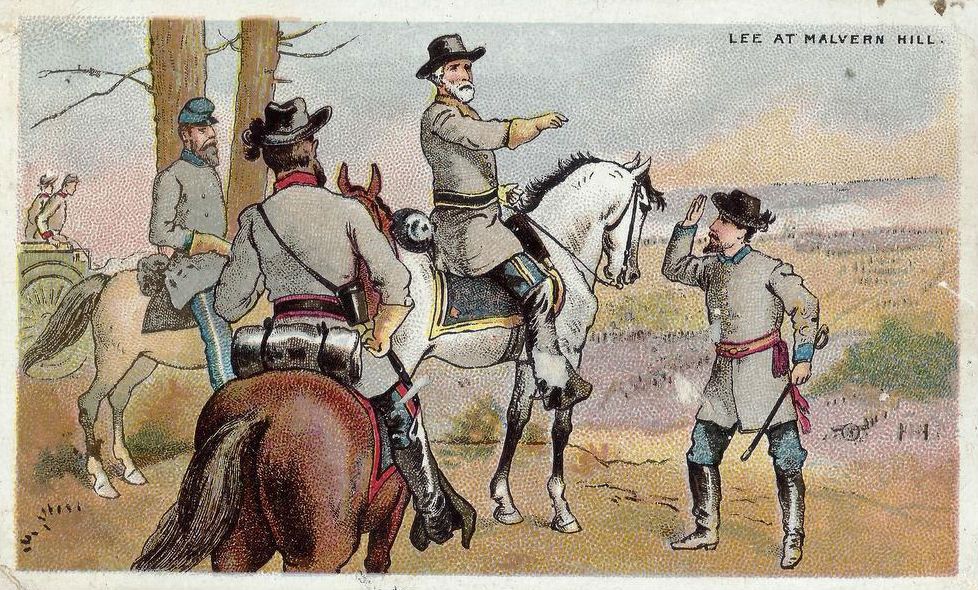

On a battlefield, the Commander preferably took an elevated position, allowing him to oversee the positions and movements of his troops as well as those of the opponent. Strategy began by positioning his troops in such a way that he could counteract most attacks while allowing him to use the elements of surprise and deception to attack his opponent. In fact, the strategy was often a playout of the various scenarios that the Commander and his seconds had discussed prior to the battle, based on past experiences, the scenary, the weather, assessments of the opponent, and available resources.

Since actual information about the enemy, observed by people on the frontline, could hardly reach the Commander or his seconds due to the noise and confusion on the battlefield, success depended very much on the elevated position of the Commander from which he could oversee the battlefield.

Additionally, a handful of scouts would try to gather information from behind enemy lines about the opponent’s movements or deceptions. However, it was a most dangerous endeavor, and many were killed before they could report their findings.

The Fatal Flaw of the 'All Eggs in One Basket' Product Launch

Now, let’s look at how companies (used to) play out their position in the marketplace. Most companies developed products based on market research. When a product had almost reached completion, which could take up to two years or more, it was subjected to a focus group, often leading to minor product alterations. When the product was finally launched, in a full-blown marketing campaign, failure was no longer an option. However, success was never a guarantee either.

As such, Sun Tzu’s principles were upheld: the CEO, as the contemporary Commander, expected his employees to be in complete accord with the surprise-and-overwhelm strategy and follow the leader without reservation or hesitation. A full-blown marketing campaign was like moving an entire battalion into battle, allowing the opponent no time to organize an adequate response. Even when customers rejected the product or complained about its quality, the battalion had to march on. There was no turning back. Many companies today still operate in this way.

The Rise of the Lean Startup

At the end of the previous century, a group of startups in Silicon Valley, often spin-offs of larger companies, had very limited resources and could not afford a surprise-and-overwhelm market entry. Instead, they adopted a mode of operation that their predecessors had already developed.

In their bestseller ‘In Search of Excellence’, McKinsey consultants Peters and Waterman identified how several multinationals that were far more successful in launching new products than their peers had operated. Peters and Waterman described how these incumbents, despite their formal management structures, encouraged employees to develop ideas for new products and handed them a tiny budget to assemble a small team and create a prototype.

Spearheaded by a product champion, the team often had to operate in stealth mode so not to disturb the morale of the rest of the company. They were asked to present and defend their product idea, based on a prototype. If they successfully convinced one member of the management team, they were allowed to test the product in the open market. Once revenue reached a certain threshold, the team was awarded more resources, essentially upscaling the operation.

Product development, essentially, came from a continuous feedback loop, in collaboration with early adopters, that eventually led to the development of a product that matched the demand of a well-defined group of customers. It all happened at the foundation of the organizational hierarchy, often out of leadership’s sight, at the level of the employee-customer interaction.

The Spearheaded Strategy

When we compare both modes of operation, incumbents versus startups, you’ll notice that the first is typically directed from a single position of high authority, distant from the frontline, while startups are directed from dispersed positions with high autonomy.

While both types of operations are being led, the word has different meanings. The command-type organization is directed on the premise of obedience and reliance on a leader’s ability to make the right calls. The spearheaded type of organization is based on the premise of personal initiatives and reliance on the employees’ ability to find new opportunities for growth, while leaders still need to make sure to drive the innovations that are most favorable.

The Peril of the High Ground: How CEOs Risk Obsolescence in a Digital Age

CEOs that apply an Art of War-type approach in today’s fast-moving market, by observing the marketplace from a high-ground position, won’t be able to see, let alone appreciate the thousands of spearheaded initiatives that are going on. Not in their own company, let alone what is going on with their opponents. When a major shift is detected from the high ground, it’s often too late to respond.

To survive in our digital age, CEOs need to rely on information obtained by people on the frontline, people who actually talk to customers. Because, based on research, CEOs spend a mere 3% of their time talking to customers. There ‘elevated’ position has become a burden and a blinder.

From Fragile to Antifragile: Why the Art of Raw Beats the Art of War in Today's Business Landscape

We live in an era of rapid breakthroughs and even faster breakdowns. It is not the time for exploitation, grand moves, bold decisions, a firm hand, or corporate heroism. It’s a time of small encouragement to explore new ideas, allow people to think outside the box, create the right circumstances for grassroots movements to blossom, and welcome failure as an opportunity for early dismissal.

When revenue starts to plummet and margins shrink, CEOs can’t afford to take months or even years to bring a polished product to market ─ only to discover that customers need something different. Unpolished is the new normal. Prototyping, collecting feedback, and iterative product development in co-creation with a small group of customers is the right way forward.

You might even imagine a modern-day, business-savvy warrior, not in a shiny suit of armor but in a worn-out hoodie, charging into the battlefield with scrappy prototypes and quick-and-dirty experiments.

This new, antifragile mode of operation is precisely the opposite of the fragile strategies taken from the Art of War. That’s why I like to call it the Art of Raw.

The new heroes in the Art of Raw are the product champions and their supporters. They typically operate in the frontline, where employees and customers interact daily, where opportunities and threats can be spotted first. And where new product ideas can be tested, as raw as it gets, to determine which ones are worth pursuing. Product champions and their supporters are the eyes and ears of the organization, picking up on market signals and customer insights that the C-suite might otherwise miss. I’m convinced that a company’s frontline operation is the Ultimate Level of Truth™.

The Four Musketeers

The image on top is taken from The Three Musketeers (1993). These frontline men are an excellent representation of a spearheaded strategy. While loyal to their king, they operate alone and below the radar, always quickly identifying and eliminating threats to the nation.

The funny thing is that there are four of them: Athos, Porthos, and Aramis, which were the original three, added with D’Artagnan, the central character of Dumas’ novel. Similarly, RoundMap identified that while most people still consider a frontline operation to consist of three departments: marketing, sales, and service, there is a missing fourth: success. The same applies to vision, mission, and strategy, where we found purpose to be the missing link. These fourths aren’t just closing the loop; they are critical to overall effectiveness, stability, and sustainability.

Author

-

Edwin Korver is a polymath celebrated for his mastery of systems thinking and integral philosophy, particularly in intricate business transformations. His company, CROSS/SILO, embodies his unwavering belief in the interdependence of stakeholders and the pivotal role of value creation in fostering growth, complemented by the power of storytelling to convey that value. Edwin pioneered the RoundMap®, an all-encompassing business framework. He envisions a future where business harmonizes profit with compassion, common sense, and EQuitability, a vision he explores further in his forthcoming book, "Leading from the Whole."

View all posts Creator of RoundMap® | CEO, CROSS-SILO.COM