Very few business transformation initiatives succeed. According to research, a staggering 70% of business transformations fail. That same number also applies to digital transformation failures, as found by McKinsey ─ punching a hole of $900 billion per year in the enterprise strategy. We believe firms need a System of Change.

Let’s start by looking at some of the identified reasons for transformation failure:

- A lack of urgency: People do not perceive an urge to change.

- A lack of aspirations: Expectations are set too low.

- No shared vision: The vision was not communicated or supported.

- No conviction: The team has no notion of the importance of change and prefers the status quo.

- No change narrative: People are not convinced they need to transform.

- No buy-in: People don’t want to invest extra energy to make change happen.

- Lack of skills: Available skills remain locked in daily jobs, prioritizing ongoing business.

- No clear procedures: No record system for directing and measuring progress.

- No change-management infrastructure: Management doesn’t know how to manage the process.

- No cadence of leadership-oversight meetings: Leadership can’t ensure progress.

- No transformation office: Or a grandmaster of change to lead the process.

- No performance management: No discussions to track progress.

- No alignment: With the vision or corporate strategy.

- No cross-team work: The heavy burden of navigating the seams within and across silos.

While there are many more reasons why business transformations continue to fail, it’s evident that the silo dynamics play a huge part. Although driving productivity, it’s hard to change existing hierarchical and functional structures, especially when people are afraid to speak out because of peer pressure or potential negative consequences. Or because of their loyalty toward their team and its leadership.

Management experts believe it is ultimately a failure of leadership that allows organizational silos to form and exist. It starts, and ultimately ends, at the top. If we can peek into the conference room of a leadership team, we will begin to see the symptoms of silos and the related causes. Watching the interactions between the members of the leadership team will usually reveal behaviors that create and enforce silos.

Minimal Requirements for Change

Certain elements must be in place in an organization for change to take hold:

- An agreed-on direction for the change,

- A functional and practical leadership structure,

- A culture that promotes and rewards change,

- The overall readiness to change.

Resistance to change is common and should be expected, according to Ana-Elena Jensen, PhD.: “Resistance to change usually comes from fear, on one of three levels:

- What will happen to me in my world,

- How will my relations with my colleagues change, or

- How will our practice and our clients be affected?

Although full schedules, distracting events, fear of change, and apathy are obstacles to change, complacency is the natural enemy of change. “Having the will to change is critical,” says consultant Fabrizio. If leaders aren’t willing to follow up on change, “stop right there.”

Transforming Toward Customer Centricity

Let’s pick an example of transformative change. Today, many companies prefer a customer-centric over a product-centric business model. But is that really what they want? Customer Centricity is about fulfilling more of a customer’s needs to obtain a more significant stake in the customers’ wallets. In contrast, a typical product-centric business model focuses on growing market share. But be careful: a stand-alone customer-centric business model isn’t sustainable (Ref. Business case: IBM).

What most firms typically want to achieve is the following:

- To retain more of their customers;

- To have them engage more often;

- To get them to share their feedback;

- To make them return more often;

- To get them to spend more over their lifetime;

- To get them to refer more often;

- To inspire them to be more loyal.

In contrast, most firms develop products for a particular customer need and then try to find as many customers as possible who want that need met. While a customer acquisition strategy is often perceived as critical to survival, few product-driven companies have a customer retention strategy. While customer service offers an excellent opportunity to help customers get their jobs done better and faster, sadly, many companies perceive customer service as an unfortunate drawback of doing business.

If a firm wants loyal customers who return more often and spend more, what must it do to make that happen?

Work Toward Customer Success

A common problem is that customers, once created, are generally left at their own devices. If firms want more loyal customers, companies should assist customers in achieving their goals. We call this practice Customer Success. Software-as-a-service (Saas) vendors are committed to Customer Success to retain more customers. Your challenge could mean setting up a Customer Success department.

Suppose you have multiple product groups, each with a dedicated sales team, and you’re selling to the same group of customers. In that case, you may consider introducing Corporate Customer Success Management (compare: corporate account management). Once the new business cycle commences, shift to corporate account management to refocus on growth.

Effective Problem Handling

- “A system is not a sum of the behavior of its parts; it’s the product of their interactions.”

- “You can not solve a problem without affecting others in the system.”

- “A separate problem can create a much more severe problem than the problem solved.”

- “You can be sure that a solution directed at improving the parts taken separately won’t improve the performance of the whole.”

- “To dissolve a problem is redesigning the organization with the problem or its environment so the problem is eliminated and cannot reappear.”

- Problem Absolution: The way we treat most problems is what Ackoff called problem absolution: we ignore the problem and hope it will eventually disappear.

- Problem Resolution: We may want to find a problem resolution, which means we look into the past to find a “good enough” solution. This approach doesn’t solve the problem but allows us to move on. The solution seldom satisfies anyone.

- Problem Solving: Our learned way of problem-solving is looking for the optimal solution, the best thing to do in the current situation. But, no problem stays solved in a dynamic environment, and every solution to improve the part that caused the problem creates new problems. So it’s a temporary and ineffective way to treat a problem.

- Problem Dissolving: The best way to create lasting change is by problem dissolving. We can only deal with a problem effectively and enduringly through (re)designing the system that has it so that the problem no longer exists.

How we solve a problem will determine the level of change needed. Absolving problems has little impact (we ignore the problem), while problem dissolving requires the most change.

Cause and Effect Analysis

Assessing the scope of a problem is part of the exercise. A good way of assessing problems is using a cause-and-effect analysis, devised by Professor Kaoru Ishikawa, a pioneer of quality management in the 1960s, often represented by a fishbone diagram. Although it was initially developed as a quality control tool, you can use the technique just as well in other ways. For instance, you can use it to discover the root cause of a problem, uncover bottlenecks in your processes, or identify where and why a process isn’t working.

Critical Thinking

What to Change

Solving a problem to improve a business process or a faulty engine part often requires change. But not all change is an improvement. W. Edward Deming developed and taught a management and improvement theory, including the Deming Cycle or the PDSA Cycle of Continuous Improvement (PDSA = Plan, Do, Check, and Act).

Deming argued that we need to ask ourselves three questions before trying to improve a system:

- What are we trying to achieve? (= Aim)

- What changes can we make that will result in an improvement? (= Change)

- How will we know that a change is an improvement? (= Measure)

We can devise the right improvement plan (CAP) by answering these questions.

Systemic and Integral Change

Systemic change involves tackling problems effectively and efficiently by either redesigning the existing system to prevent recurring issues (system improvement) or adopting an entirely new system (transformative change). However, it’s crucial to understand that the scope of the system extends beyond processes and structures to encompass individuals, teams, and leadership. Ensuring the success of change initiatives often requires adjustments in people’s behavior, employee skill development, enhanced emotional and social awareness to foster teamwork and collaboration, and guidance from the leadership team. When change is viewed holistically, considering the individual, the team, and the entire system, it is referred to as integral change, recognizing that meaningful transformation encompasses both processes and the human and organizational dimensions.

Advancing Horizontal Collaboration

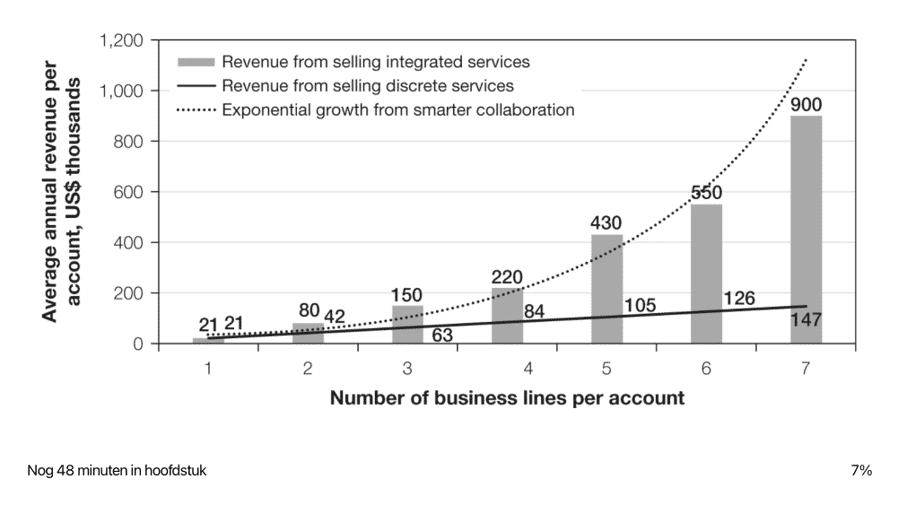

In her research, Harvard’s Heidi K. Gardner Ph.D. found that: ‘For professional services firms, the only way to address the client’s most complex issues is for specialists to work together across the boundaries of their expertise.’

Cross-functional or horizontal collaboration has become critical in today’s complex world and is paying off. Heidi Gardner stated, ‘Organizations earn higher margins, inspire greater customer loyalty, produce more innovative work, and attract and retain the best talent when specialists engage in smart collaboration across boundaries.’ We couldn’t agree more: next to having a growth mindset, a collaborative mindset is essential for coping with today’s challenges.

As we’ve stated numerous times on our corporate website and this website, employees have narrowed down their expertise. At the same time, conditions today are more volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (VUCA) than ever before. To cope with today’s complex problems (like the issues related to the pandemic, global competition, digitalization, and virtualization), ‘experts need to integrate their specialized knowledge to tackle more complex problems than any of them could do alone’ as Heidi so eloquently described in a webinar.

A recent study by McKinsey revealed that positive employee experiences (EX) lead to 16 times more employee engagement and that they are 8 times more likely to want to stay at the company: “How do leaders satisfy all parties in trying to remake the mission? In our view, they have a unique opportunity to listen to their employees and engage them on what matters—now and into the future”, as found by McKinsey, “Workers are hungry for trust, social cohesion, and purpose. They want to feel that their contributions are recognized and that their team is collaborative. They desire clear responsibilities and opportunities to learn and grow. They expect their sense of purpose to align with that of their organization. And they want an appropriate physical and digital environment that gives them the flexibility to achieve that elusive work–life balance.

Collaboration across different parts of a business can bring significant benefits, but it can also be challenging to get people to work together. Some high-performing individuals within the organization may attribute their success to working independently, so they might resist changing their behavior. Moreover, functional silos often create distinct subcultures within the company, with their specialized language, heroes, reward systems, and loyalties. This can make it seem unappealing to collaborate with those who have different perspectives. Additionally, sharing information openly might not seem advantageous if hoarding information provides a sense of leverage or bargaining power.

However, it’s essential to recognize that, as highlighted by Gardner, having a collaborative mindset is crucial for dealing with the significant challenges modern companies face in today’s fast-paced world. Many books discuss breaking down silos, but our approach focuses on starting with those who are willing to embrace change rather than battling against those who resist it. By demonstrating that collaboration leads to positive outcomes and addressing their concerns, we can win over those who initially opposed it, allowing the barriers between silos to dissolve naturally.

Navigating Change Circles

In these challenging times filled with opportunities and threats, companies must establish platforms where employees and management can collaborate effectively. This collaboration involves sharing ideas, discussing customer issues, and addressing immediate problems. Such platforms should also serve as spaces for exploring new opportunities and swiftly identifying potential threats.

To achieve this without the need for a complete overhaul of the existing organizational structure, we propose a straightforward solution known as “Change Circles” or roundtables. Change Circles provide a safe environment where individuals can freely express their thoughts and engage in discussions that transcend the organization’s usual mental and functional barriers. This collaborative setting encourages a transdisciplinary perspective on opportunities and threats, enabling the development of impactful initiatives for change.

Why use roundtables? As found by astute authors like Heidi Gardner, Patrick Lencioni, and Gillian Tett, crossing the silos is critical but also extremely difficult. At the same time, the urge to collaborate from diverse backgrounds is extremely high. Companies need a resolution NOW and can’t always afford to go through a tedious process of cultural transformation to get people to work across the silos.

Change Circles should focus on explaining the why, how, and what of change. When individuals understand why a change is necessary, they are more likely to be receptive to the specifics of how and what needs to change. Moreover, if around 15% of people within an organization commit to the change, it often paves the way for others to follow suit.

For example, during a Customer Roundtable discussion about the growing customer turnover rate, participants identified a solution to address this issue: implementing customer success management to enhance the customer onboarding process. Subsequently, members of the Business Roundtable discussed and agreed upon this Change Proposal (CP), leading to the endorsement of a Change Recommendation. This recommendation was then forwarded to the Change Management Office to kickstart a Change Action Plan (CAP), with the support of a senior management member referred to as the CAPtain.

It’s crucial to emphasize that it is essential to maintain alignment between Change Circles and the company’s existing (or desired) vision, strategy, purpose, and mission. This alignment ensures that individuals remain focused on the intended direction of change and do not veer off in various directions.

![Catalyzing Organizational Transformation: The Power of Change Circles 4 ROUNDMAP_Change_Circles_Diagram_Copyright_Protected_2022[1]](https://roundmap.com/wp-content/uploads/ROUNDMAP_Change_Circles_Diagram_Copyright_Protected_20221-1024x1024.png)

Navigating the Change Map

In addition to utilizing Change Circles, we incorporate a tool called the Change Map to serve as a guiding framework for achieving transformative change, based on the principles of the Change Canvas.

The Change Map is a visual mapping system designed to help outline several vital aspects. It facilitates the description of both the current state and the desired future state and identifies the necessary changes in terms of culture and behavior, processes, technology, talent and capabilities, and organizational structure. Furthermore, it outlines the essential elements for change, such as communication strategies and training plans.

Our approach to change is characterized by a collective effort driven by storytelling. It balances the traditional top-down diagnostic approach advocated by figures like Lewin, Kotter, and Mauser and a more grassroots dialogic approach. Change Circles can serve as meeting points for a Change Coalition in the context of transformative change. In a future post, we’ll delve into more details about the Change Map.

Commercial versus Operational

Change Circles (CCs) and Change Maps (CMs) intend to drive change, for instance, by improving customer value creation, transitioning from a product-driven to a customer-driven organization, or changing from a fixed to a growth mindset to become a more creative, collaborative, and innovative organization.

You might be familiar with a more traditional counterpart, Quality Circles. A Quality Circle (QC) is a participatory management technique to manage and improve the quality of the entire organization. Similar to the CC, the power of a QC comes from mutual trust between managers and employees, which leads to more mutual understanding that focuses on improving the attitude toward quality throughout the organization.

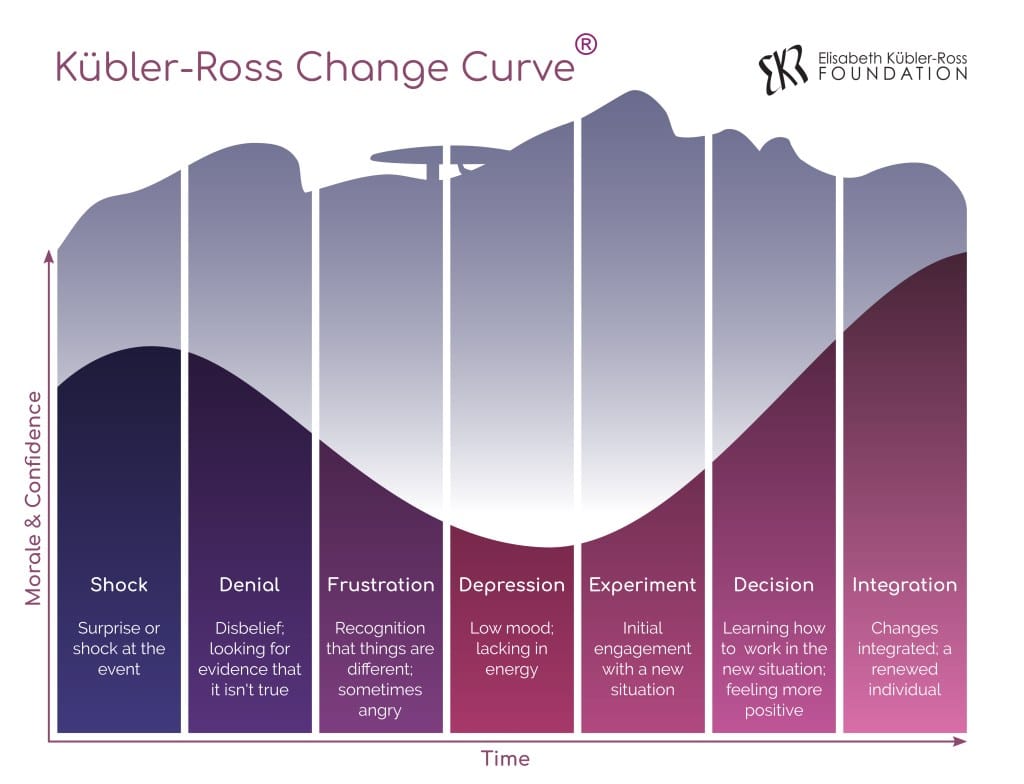

We’ve enriched our concept of Change Circles with Ackoff’s four ways of problem handling (absolve, resolve, solve, and dissolve) and the Kubler-Ross Change Curve. We’ve also included the four ‘cornerstones’ (vision, strategy, purpose, and mission) as inspiration, should you want to divide the roundtables hierarchically over the four cornerstones.

Change Action Plan or CAP

A Change Request can be turned into a systemic Change Action Plan (CAP). Suppose you haven’t assembled a Change Coalition to make transformative change happen. In that case, we recommend appointing a CAP Officer or setting up a CAP Office to ensure that CAPs can be executed successfully. If a CAP is transformational to the business, you could appoint a Transformation Officer or a Transformation Management Office (top-down approach). But again, if you want the entire organization to be involved in change, we strongly advise assembling a Change Coalition.

A recent post by Greg Satell can be seen as a warning but don’t get discouraged by it: “Change fails because people want it to fail. Any important change with the potential for real impact will inspire fierce resistance. Some people will hate the idea and try to undermine your efforts in dishonest, deceptive, and underhanded ways,” and “People who hate your idea are, in large part, trying to persuade many of the same people you are. Listening to which arguments they find effective can help unlock shared values, which holds the key to truly transformational change.”

Kubler-Ross Change Curve®

Change can have an impact. In the image above, we’ve incorporated the Change Curve (on the outer rim, anti-clockwise, implying an evolutionary process) to explain the relationship between problems, lasting change, and the emotional response to change interventions. Since its formation, individuals and organizations have extensively used the Kübler-Ross model or the Kübler-Ross Change Curve model to help people understand their reactions to significant change or loss. The Kubler-Ross Change Curve model is widely accepted to explain the response to change. As the basic human emotions experienced during personal loss, Change, death, or a dramatic experience remain the same, this model can be applied effectively in such situations.

Author

-

Edwin Korver is a polymath celebrated for his mastery of systems thinking and integral philosophy, particularly in intricate business transformations. His company, CROSS/SILO, embodies his unwavering belief in the interdependence of stakeholders and the pivotal role of value creation in fostering growth, complemented by the power of storytelling to convey that value. Edwin pioneered the RoundMap®, an all-encompassing business framework. He envisions a future where business harmonizes profit with compassion, common sense, and EQuitability, a vision he explores further in his forthcoming book, "Leading from the Whole."

View all posts Creator of RoundMap® | CEO, CROSS-SILO.COM

![Catalyzing Organizational Transformation: The Power of Change Circles 2 ROUNDMAP_Ackoff_Productivity_Matrix_Copyright_Protected[1]](https://roundmap.com/wp-content/uploads/ROUNDMAP_Ackoff_Productivity_Matrix_Copyright_Protected1.png)